Thursday, December 12, 2013

A History of Veronica, 02: Abgar and the Image of Jesus, Part 01

Picking up where I left off:

It is in the 8th century that in the West we begin to see Berenice/Veronica connected with an image of Jesus on a piece of cloth. But, before we get to that, let's first talk about the earlier story of King Abgar and the image of Jesus he received known as the Mandylion.

A History of Veronica, 01: The Woman

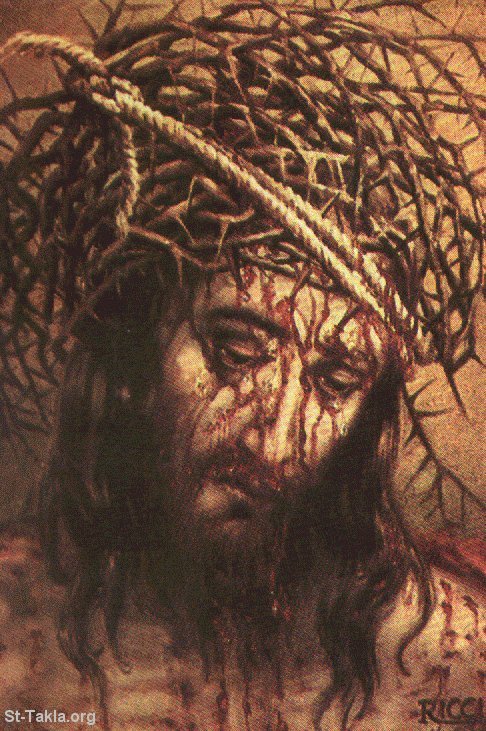

If you're Catholic, chances are you've probably heard of Veronica and her veil by which she wiped Jesus' face as He carried His cross to Golgotha. Despite her not being found in the New Testament, she is commemorated in the sixth Station of the Cross, and in addition, some Jesus films choose to include her in some form or another - examples of this would include Jesus of Nazareth or The Passion of the Christ (the clip below). The story is popular, methinks, because it epitomizes compassion: a woman helping the Lord in the smallest way she could in His hour of need and being rewarded for it in the form of an image on her veil.

But here's the thing. What do we really know about the woman we call 'Veronica'? And how did her story develop over time? And what does the so-called 'veil' of Veronica have to do with it?

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

The Minor, Trivial Biblical Stuff, Part 11: Ancient Writers on the Cross

A Roman citizen of no obscure station, having ordered one of his slaves to be put to death, delivered him to his fellow-slaves to be led away, and in order that his punishment might be witnessed by all, directed them to drag him through the Forum and every other conspicuous part of the city as they whipped him, and that he should go ahead of the procession which the Romans were at that time conducting in honour of the god. The men ordered to lead the slave to his punishment, having stretched out both his arms and fastened them to a piece of wood which extended across his breast and shoulders as far as his wrists, followed him, tearing his naked body with whips.-Dionysius of Halicarnassus (ca. 60 BC-after 7 BC), Roman Antiquities, VII, 69:1-2

I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet (patibulum).-Seneca the Younger (ca. 1 BC-AD 65), To Marcia on Consolation, 20.3

Such are his verbal offences against man; his offences in deed remain. Men weep, and bewail their lot, and curse Cadmus with many curses for introducing Tau (Τ) into the family of letters; they say it was his body that tyrants took for a model, his shape that they imitated, when they set up the erections on which men are crucified. Σταυρός (stauros) the vile engine is called, and it derives its vile name from him. Now, with all these crimes upon him, does he not deserve death, nay, many deaths? For my part I know none bad enough but that supplied by his own shape--that shape which he gave to the gibbet named σταυρός after him by men.-Pseudo-Lucian (ca. 125-after 180), Trial in the Court of Vowels

Saturday, August 21, 2010

The Minor, Trivial Biblical Stuff, Part 7: The Nails of the Crucifixion

The oldest depiction of a crucifixion we have, the Alexamenos Graffito (dating from the late 1st-3rd century AD), clearly shows the crucified figure's feet as being separate. Other early images, such as a late 2nd-3rd century carved jasper either from Syria or Gaza (part of the Pereire Collection), a graffito found in Puzzuoli, another gem, and a relief from Santa Sabina in Rome (ca. 430-435 AD), follow suit in not showing the feet as being placed above the other. This convention has passed on to later Christian iconography, and for a time people, both in the East and the West, portrayed Jesus Christ being crucified with His feet separate.

Saturday, June 19, 2010

The Minor, Trivial Biblical Stuff, Part 3: 'Mount' Calvary

And they took Jesus and led Him away, and carrying the cross by Himself, He went out to the place called Place of a Skull (which is called in Hebrew 'Golgotha'), where they crucified Him, and with Him two others: on this side and on that side, but in the middle Jesus.Nowadays, it is common to assume that the Golgotha of the Gospels was a sort of hill located a good distance from the hustle-and-bustle of Jerusalem (hence the common appellation: ‘Mount Calvary’). Many artists and filmmakers have followed suit: sometimes to the extent of showing it as a very high and steep ridge, as Mel Gibson does in his famous film The Passion of the Christ. There are even hymns entitled There is a Green Hill Far Away or On Golgotha's Hill Christ the Son.

- John 19:16b-18

Close reading of the Gospel accounts themselves however do not say anything about the location, whether it was a hill – or for that matter, that the ‘Skull Place’ was an elevated area at all; they all just say something to the effect that it was a “place (Greek topos) called ‘Skull’.” This may be one of the cases where popular conception can color our reading of the Scriptures.

Sunday, March 29, 2009

The Garden Tomb: a grave from the Iron Age?

ngland originally committed itself to the site as the place of Jesus' burial and "Gordon's Tomb" became the "Garden Tomb." The Church has since withdrawn its formal support, but the Garden Tomb continues to be identified by popular Protestant piety.

ngland originally committed itself to the site as the place of Jesus' burial and "Gordon's Tomb" became the "Garden Tomb." The Church has since withdrawn its formal support, but the Garden Tomb continues to be identified by popular Protestant piety.Sunday, September 21, 2008

On Crucifixion: An Essay: part 3

As mentioned, giving the victim a proper burial following death on the cross during the Roman period was rare and in most cases simply not permitted in order to continue the humiliation - it was common for Romans to deny burial to criminals, as in the cases of Brutus and his supporters (Suetonius, Augustus 13.1-2) and Sejanus and company (Tacitus, Annals 6.29). The corpse was in many cases either simply thrown away on the garbage dump of the city, 'buried' in a common grave, or left on the cross as food for wild beasts and birds of prey.

As mentioned, giving the victim a proper burial following death on the cross during the Roman period was rare and in most cases simply not permitted in order to continue the humiliation - it was common for Romans to deny burial to criminals, as in the cases of Brutus and his supporters (Suetonius, Augustus 13.1-2) and Sejanus and company (Tacitus, Annals 6.29). The corpse was in many cases either simply thrown away on the garbage dump of the city, 'buried' in a common grave, or left on the cross as food for wild beasts and birds of prey.Petronius, in the Satyricon (111), writes an amusing - to the Romans at least - story about a soldier who was tasked to guard the body of some crucified criminals from theft. The soldier manages to lose one of the corpses, however, when he diverts his attention from the crosses in order to pursue an amorous interlude with a widow mourning for the loss of her husband (who was buried near the execution site):

...Thus it came about that the relatives of one of the malefactors, observing this relaxation of vigilance, removed his body from the cross during the night and gave it proper burial. But what of the unfortunate soldier, whose self-indulgence had thus been taken advantage of, when next morning he saw one of the crosses under his charge without its body! Dreading instant punishment, he acquaints his mistress with what had occurred, assuring her he would not await the judge's sentence, but with his own sword exact the penalty of his negligence. He must die therefore; would she give him sepulture, and join the friend to the husband in that fatal spot?Beyond the baudiness and light-heartedness of the anecdote lies the seriousness with which Romans could take the matter of guarding victims: the soldier guards the crosses for three nights, and fears for his life when the theft is discovered.

But the lady was no less tender-hearted than virtuous. 'The Gods forbid,' she cried, 'I should at one and the same time look on the corpses of two men, both most dear to me. I had rather hang a dead man on the cross than kill a living.' So said, so done; she orders her husband's body to be taken from its coffin and fixed upon the vacant cross. The soldier availed himself of the ready-witted lady's expedient, and next day all men marveled how in the world a dead man had found his own way to the cross.

The prevention of burial also serves to show a graphic display of the power of the Roman Empire: by not allowing the victims even a decent burial, it is declared that the loss of these victims is not a loss to society, but far from it, they actually served to strengthen and empower Rome, ridding the Empire of its enemies and maintaining the status quo and preserving law and order.

Because of these details, some, like John Dominic Crossan, suggest controversially that it was improbable that Jesus was given a proper burial, as the Gospels relate; instead, he might have been thrown in the waste dump in Jerusalem. Indeed, there were times in which Roman officials in Judea behaved like their counterparts in other areas of the Empire. When Publius Quinctilius Varus, then Legate of Syria, moved into Judea in 4 BC to quell a messianic revolt after the death of Rome's client king Herod the Great, he reportedly crucified 2000 Jewish rebels in and around Jerusalem (Josephus, Antiquities 17.295). Later, the procurator of Judea, Gessius Florus is said to have ordered indiscriminate crucifixions, including those who were actually Roman citizens (Josephus, Jewish War 2.306-7). And, finally, in 70 AD, the general Titus ordered hundreds of Jewish captives to be crucified around the walls of Jerusalem in the hopes that this would drive the Jews to surrender (Jewish War 5.450). Josephus does not state explicitly that the bodies were left hanging, but that would be entirely consistent with the general purpose of these crucifixions.

Even so, one needs to consider the situation of the Province of Judea within the time of Jesus: at that time the situation was (in one sense) peaceful enough that events in and around Jerusalem were not always under control of the Prefect of Judea. While there is a small contingent of soldiers stationed in Antonia Fortress, the day-to-day government of the city is largely left to Jewish hands, specifically the high priest and the council, who were accountable to the Prefect (in this period, Pontius Pilate). The Prefect in turn was accountable to the Legate of Syria, and it was the interest of all to keep the status quo undisrupted. It would then be a mistake to assume that episodes like those of Varus, Florus, and Titus are typical of the situation surrounding Jesus' burial.

However, taking victims of crucifixion down from their crosses and burying them was not unheard of. Philo (Flacc. 10.83-84) tells us that:

"I actually know of instances of people who had been crucified and who, on the moment that such a holiday was at hand, were taken down from the cross and given back to their relatives in order to give them a burial and the customary rites of the last honors. For it was (thought to be) proper that even the dead should enjoy something good on the emperor's birthday and at the same time that the sanctity of the festival should be preserved. Flaccus, however, did not order to take down people who had died on the cross but to crucify living ones, people for whom the occasion offered amnesty, to be sure only a short-lived not a permanent one, but at least a short postponement of punishment if not entire forgiveness."Josephus (Jewish War 4.5.2) relates that Jews took down the bodies of those who were crucified during the Great Revolt, as is the command in Deuteronomy 21:22-23 ("When someone is convicted of a crime punishable by death and is executed, and you hang him on a tree, his corpse must not remain all night upon the tree; you shall bury him that same day, for anyone hung on a tree is under God's curse"). In Jewish thought, giving a proper interment for someone -- even the dead of their enemies -- was considered to be ritual piety (2 Sam. 21:12-14):

In a few cases, concessions can be made if relatives or friends of the victim asked for the corpse to give it a decent burial. The discovery of the bones of a victim who died of crucifixion discovered in 1968 (see below) within an ossuary inside a tomb may suggest that giving proper burial to crucifixion victims (as in the case of Jesus), while being rather rare, was not unknown."...But the rage of the Idumeans was not satiated by these slaughters; but they now betook themselves to the city, and plundered every house, and slew every one they met; and for the other multitude, they esteemed it needless to go on with killing them, but they sought for the high priests, and the generality went with the greatest zeal against them; and as soon as they caught them they slew them, and then standing upon their dead bodies, in way of jest, upbraided Ananus with his kindness to the people, and Jesus (ben Ananias) with his speech made to them from the wall.

Nay, they proceeded to that degree of impiety, as to cast away their dead bodies without burial, although the Jews used to take so much care of the burial of men, that they took down those that were condemned and crucified, and buried them before the going down of the sun. I should not mistake if I said that the death of Ananus was the beginning of the destruction of the city, and that from this very day may be dated the overthrow of her wall, and the ruin of her affairs, whereon they saw their high priest, and the procurer of their preservation, slain in the midst of their city..."

IV. ARCHEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Despite being mentioned in many literary sources for the Roman period, few exact details as to how the condemned were affixed to the cross have come down to us. But we do have one unique archeological witness to this gruesome practice.

Despite being mentioned in many literary sources for the Roman period, few exact details as to how the condemned were affixed to the cross have come down to us. But we do have one unique archeological witness to this gruesome practice. In 1968, building contractors working in Giv'at haMivtar (Ras el-Masaref), just north of Jerusalem near Mount Scopus and immediately west of the road to Nablus accidentally uncovered a Jewish tomb dated to the 1st century AD. The date of the tombs, revealed by the pottery in situ, ranged from the late 2nd century B.C. until 70 A.D.

In 1968, building contractors working in Giv'at haMivtar (Ras el-Masaref), just north of Jerusalem near Mount Scopus and immediately west of the road to Nablus accidentally uncovered a Jewish tomb dated to the 1st century AD. The date of the tombs, revealed by the pottery in situ, ranged from the late 2nd century B.C. until 70 A.D.These family tombs with branching chambers, which had been hewn out of soft limestone, belong to the Jewish cemetery of Jesus' time that extends from Mount Scopus in the east to the tombs in the neighborhood of Sanhedriya (named after the Jewish Sanhedrin; it is not certain, however, whether the tombs, which are occupied by seventy people of high status, were the burial places of Sanhedrin officials), in the north west.

A team of archeologists, led by Vassilios Tzaferis, found within the caves the bones of thirty-five individuals, with nine of them apparently having a violent death. Three children, ranging in ages from eight months to eight years, died from starvation. A child of almost four expired after much suffering from an arrow wound that penetrated the left of his skull (the occipital bone). A young man of about seventeen years burned to death cruelly bound upon a rack, as inferred by the grey and white alternate lines on his left fibula. A slightly older female also died from conflagration. An old women of nearly sixty probably collapsed from the crushing blow of a weapon like a mace; her atlas, axis vertebrae and occipital bone were shattered. A woman in her early thirties died in childbirth, she still retained a fetus in her pelvis.

The late Professor Nicu Haas, an anthropologist at the Anatomy School at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem-Hadassah Medical School, examined one of the bones, which were placed inside a stone ossuary (right) placed inside one of the tombs which bears the Hebrew inscription ‘'Yehohanan the son of Hagaqol'. The bones were those of a man in his twenties, crucified probably between 7 A.D., the time of the census revolt, and 66 A.D., the beginning of the war against Rome. The evidence for this was based on the right heel bone, pierced by an iron nail 11.5 centimetres in length. The nail penetrated the lateral surface of the bone emerging on the middle of the surface in which the tip of the nail had become bent. The bending of the tip upon itself suggests that after the nail penetrated the tree or the upright it may have struck a knot in the wood thereby making it difficult to remove from the heel when Yehohanan was taken down from the cross.

The point of the nail had olive wood fragments on it indicating that Yehohanan was crucified on a cross made of olive wood or on an olive tree, which would suggest that the condemned was crucified at eye level since olive trees were not very tall. Additionally, a piece of acacia wood was located between the bones and the head of the nail, presumably to keep the condemned from freeing his foot by sliding it over the nail. Yehohanan's legs were found broken, perhaps as a means of hastening his death (Crucifragium; cf. John 19:31-32).

Haas asserted that Yehohanan experienced three traumatic episodes: the cleft palate on the right side and the associated asymmetries of his face likely resulted from the deterioration of his mother's diet during the first few weeks of pregnancy; the disproportion of his cerebral cranium (pladiocephaly) were caused by difficulties during birth. All the marks of violence on the skeleton resulted directly or indirectly from crucifixion.

Furthermore, despite the original belief that evidence for nailing was found on the radius, a subsequent reexamination of the evidence showed that there was no evidence for traumatic injury to the forearms; various opinions have since then been proposed as to whether the feet were both nailed together to the front of the cross or one on the left side, one on the right side, and whether Yehohanan's hands was actually nailed to the cross or merely tied (Zias' reconstruction of Yehohanan's posture, at right).

Furthermore, despite the original belief that evidence for nailing was found on the radius, a subsequent reexamination of the evidence showed that there was no evidence for traumatic injury to the forearms; various opinions have since then been proposed as to whether the feet were both nailed together to the front of the cross or one on the left side, one on the right side, and whether Yehohanan's hands was actually nailed to the cross or merely tied (Zias' reconstruction of Yehohanan's posture, at right).While the archeological and physiological record are mostly silent on crucifixion, there are possibilities which may account for this: one is that most victims may have been tied to the cross, which would explain the lack of any direct traumatic evidence on the human skeleton when tied to the cross. The other is that the nails were usually either reused or taken as medical amulets, as stated in part 1.

V. SOURCES and FURTHER READING

1.) Wikipedia's articles on Crucifixion, Flagellation, Cross or stake as gibbet on which Jesus died, and Crucifixion of Jesus

2.) Crucifixion in Antiquity by Joe Zias

3.) Forensic and Clinical Knowledge of the Practice of Crucifixion by Frederick Zugibe

4.) On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ, by William D. Edwards, M.D., Wesley J. Gabel, MDiv, and Floyd E. Hosmer, MS, AMI

5.) The Catholic Encyclopedia's articles on Archeology of the Cross and Crucifix and Holy Nails

6.) International Standard Bible Encyclopedia's article on Cross

7.) Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible's entry on Crucifixion

8.) Josephus' References to Crucifixion, from The Jewish Roman world of Jesus

9.) National Geographic's documentary Quest for Truth: The Crucifixion: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, and part 6 viewable here

10.) New Testament History's entry on Crucifixion

11.) Crucifixion, from Richard Stracke's site on Christian Iconography

Saturday, September 20, 2008

On Crucifixion: An Essay: part 2

Blood loss from the scourging helped determine the time the victim survived. In any case, victims suffered a long time (at most, days) before falling into prolonged unconsciousness and death. Soldiers typically did not hasten things along because a long and painful death was the point of the execution method. Usually the victim was left on the cross until birds and wild beasts consumed the body.

Blood loss from the scourging helped determine the time the victim survived. In any case, victims suffered a long time (at most, days) before falling into prolonged unconsciousness and death. Soldiers typically did not hasten things along because a long and painful death was the point of the execution method. Usually the victim was left on the cross until birds and wild beasts consumed the body.Death could result from a variety of causes, including blood loss and hypovolemic shock, or infection and sepsis, caused by the scourging that preceded the crucifixion or by the nailing itself, and eventual dehydration. A theory attributed to French surgeon Dr. Pierre Barbet (author of A Doctor at Calvary: The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ As Described by a Surgeon) holds that, when the whole body weight was supported by the stretched arms, the typical cause of death was asphyxiation. He conjectured that the condemned would have severe difficulty inhaling, due to hyper-expansion of the chest muscles and lungs.

The condemned would therefore have to draw himself up by his arms, leading to exhaustion, or have his feet supported by tying or by a wood block. Indeed, the executioners were sometimes asked that the legs of the victim were broken or shattered, an act called crucifragium which was also frequently applied without crucifixion to slaves.

This act speeded up the death of the person but was also meant to deter those who observed the crucifixion from committing offenses. Once deprived of support and unable to lift himself, the victim would die within a few minutes.

Experiments by Dr. Frederick Zugibe, former chief medical examiner of Rockland County, New York have revealed that, when suspended with arms at 60° to 70° from the vertical, test subjects had no difficulty breathing, only rapidly-increasing discomfort and pain. This would correspond to the Roman use of crucifixion as a prolonged, agonizing, humiliating death. Zugibe claims that the breaking of the crucified condemned's legs to hasten death was administered as a coup de grâce, causing severe traumatic shock or hastening death by fat embolism. Crucifixion on a single pole with no transom, with hands affixed over one's head, would precipitate rapid asphyxiation if no block was provided to stand on, or once the legs were broken.

It is possible to survive crucifixion, if not prolonged, and there are records of people who did. The historian Josephus, a Judean who defected to the Roman side during the Jewish uprising of 66-72 AD, describes finding two of his friends crucified. He begged for and was granted their reprieve; one died, while the other recovered. Josephus gives no details of the method or duration of their crucifixion before their reprieve.

E. WERE VICTIMS CRUCIFIED NAKED? It is still a matter of debate whether victims were crucified in the nude or with their loincloths left on. There is no doubt that many (if not most) crucifixion victims were stripped naked, either with or without a loincloth, as it would have humiliated the victim further. This is one of the elements which made crucifixion notorious: due to the physical, mental and emotional pain it caused.

It is still a matter of debate whether victims were crucified in the nude or with their loincloths left on. There is no doubt that many (if not most) crucifixion victims were stripped naked, either with or without a loincloth, as it would have humiliated the victim further. This is one of the elements which made crucifixion notorious: due to the physical, mental and emotional pain it caused.

While traditionally Jesus and the two criminals are depicted as having a sort of loincloth for modesty (in a few depictions, Jesus even wears a full-length robe, called a colobium), a few very early depictions depict the victim as either being stark naked on the cross or with some loincloth on (also see illustration at left and below right, one of which is a graffito found in Puzzuoli, with the other being a gem found in Syria, dating from the late 2nd-3rd century). As a general rule of thumb, most of these early representations are not depictions made by Christians, who still didn't depict the Crucifixion overtly during this time period, but were usually created by non-Christians and/or Gnostics.

As a general rule of thumb, most of these early representations are not depictions made by Christians, who still didn't depict the Crucifixion overtly during this time period, but were usually created by non-Christians and/or Gnostics.

While some take the position that Jesus was not spared even a loincloth when He was crucified, some believe that due to Jewish sensibilities, loincloths were left on or provided (it would be fitting to remind here that many people in ancient times did not even wear loincloths; for them, their tunics served as their undergarment). So, before we could have any conclusive evidence, it would seem that the best answer here for the moment is that it depended on the situation and the location.

F. THE SHAPE OF THE CROSS

The gibbet on which crucifixion was carried out could be of many shapes. Josephus records multiple tortures and positions of crucifixion during the Siege of Jerusalem as Titus crucified the rebels; and the Roman historian Seneca the Younger recounts ("To Marcia, On Consolation", 6.20.3):

"Video istic cruces non unius quidem generis sed aliter ab aliis fabricatas: capite quidam conversos in terram suspendere, alii per obscena stipitem egerunt, alii brachia patibulo explicuerunt. Video fidiculas, video verbera, et membris singulis articulis singula docuerunt machinamenta: sed video et mortem..."At times the gibbet was only one vertical stake, called in Latin crux simplex or palus. This was the simplest available construction for torturing and killing the criminals. Frequently, however, there was a cross-piece attached either at the top to give the shape of a T (crux commissa) or just below the top, as in the form most familiar in Christian symbolism (crux immissa). Other forms were in the shape of the letters X and Y.

I see there crosses, not merely of one kind but fashioned differently by others: a certain one suspends with head down towards the ground, others drive stakes through their private parts; others stretch the arms out on the gibbet; I see cords, I see whips, and contraptions designed to torture every joint and limb, but I see death as well...

While the view that Jesus died on a stake has thus been propounded by writers of the nineteenth and twentieth century (and is still popular among Jehovah's Witnesses), second-century writers, such as Justin Martyr and Irenaeus, who were much closer to the event, speak of him only as dying on a two-beam cross.

In the same century, the author of the Epistle of Barnabas and Clement of Alexandria saw a two-beam shape of the cross of Jesus as foreshadowed in a numerological interpretation of Genesis 4:14, and the first of these, as well as Justin Martyr, saw the same shape prefigured in Moses keeping his arms stretched out in prayer in the battle against Amalek. At the end of the same century, Tertullian speaks of Christians as accustomed to mark themselves repeatedly with the sign of the cross, and the phrase "the Lord's sign" (τὸ κυριακὸν σημεῖον, to Kyriakon simeion) was used with reference to a cross composed of an upright and a crossbeam. Crosses of † or Τ shape were in use, even in Palestine, at the time of Jesus.

See here for more in-depth discussion on the shape of Jesus' cross.

G. LOCATION OF THE NAILS

In popular depictions of crucifixion, the condemned is shown with nails in the palm of their hands. Although historical documents refer to the nails being in the hands, the word usually translated as hand, "χείρ" (cheir) in Greek, referred to arm and hand together, so that, words are added to denote the hand as distinct from the arm, as "ἄκρην οὔτασε χεῖρα" (Akrin outase cheira, "he wounded the end of the 'cheir'", i.e. he wounded her hand).

A possibility that does not require tying is that the nails were inserted just above the wrist, between the two bones of the forearm (the radius and the ulna). The nails could also be driven through the wrist, in a space between four carpal bones. The word χείρ, translated as "hand", can include everything below the mid-forearm: Acts 12:7 uses this word to report chains falling off from Peter's 'hands', although the chains would be around what we would call wrists. This shows that the semantic range of χείρ is wider than the English hand, and can be used of nails through the wrist.

An experiment that was the subject of National Geographic Channel's documentary entitled Quest For Truth: The Crucifixion, and of a brief news article, showed that a person can be suspended by the palm of their hand. Nailing the feet (or the ankles) to the side of the cross relieves strain on the wrists by placing most of the weight on the lower body.

Another possibility, suggested by Frederick Zugibe, is that the nails may have been driven in at an angle, entering in the palm in the crease that delineates the bulky region at the base of the thumb, and exiting in the wrist, passing through the carpal tunnel.

A footrest attached to the cross, perhaps for the purpose of taking the man's weight off the wrists, is sometimes included in representations of the crucifixion of Jesus, but is not mentioned in ancient sources. These, however, do mention the sedile (a small piece or block of wood attached to the front of the cross, about halfway down, where the victim could rest) which could have served that purpose.

H. THE NUMBER OF THE NAILS USED IN JESUS' CRUCIFIXION

The question has long been debated whether Jesus was crucified with three or with four nails.

The treatment of the Crucifixion in art during the earlier Middle Ages strongly supports the tradition of four nails, and the language of certain historical writers (none, however, earlier than Gregory of Tours, "De Gloria Martyrum", vi), favors the same view. The earliest depictions of the subject (see links to pictures in Section E above) might also favor this view, as they generally depict the feet of the victim as being separate from each other.

On the other hand, in the thirteenth century, most of Western art (with a few exceptions; see the image to the right, painted by Diego Velázquez in 1632) began to represent the feet of Jesus as placed one over the other and pierced with a single nail. This accords with the language of Nonnus and Socrates and with the poem "Christus Patiens" attributed to St. Gregory Nazianzus, which speaks of three nails.

This depiction of three nails had actually caused some controversy when it was first introduced. For example, in the latter part of the 13th century the bishop of Tuy in Iberia wrote in horror about the 'heretics' who carve 'ill-shapen' images of the crucified Jesus 'with one foot laid over the other, so that both are pierced by a single nail, thus striving to annul or render doubtful men's faith in the Holy Cross and the traditions of the sainted Fathers.'

Archaeological criticism has pointed out however not only that two of the earliest representations of the Crucifixion (the Palatine graffito does not here come into account), viz., the carved door of the Santa Sabina in Rome, and the ivory panel of the British Museum, show no signs of nails in the feet, but that St. Ambrose ("De obitu Theodosii" in P.L., XVI, 1402) and other early writers distinctly imply that there were only two nails. However, this does not answer why in Luke 24:39-40 Jesus is said to have shown 'his hands and his feet' to his disciples, unless there was some distinguishing mark located there.

St. Ambrose informs us that Empress Helena had one nail converted into a bridle for Constantine's horse (early commentators quote Zechariah 14:20, in this connection), and that an imperial diadem was made out of the other nail. Gregory of Tours speaks of a nail being thrown (deponi), or possibly dipped into the Adriatic Sea to calm a storm. It is impossible to discuss these problems adequately in brief space, but the information derivable from the general archaeology of the punishment of crucifixion as known to the Romans does not in any way contradict the early Christian tradition of four nails.

On Crucifixion: An Essay: part 1

I. INTRODUCTION

Crucifixion (from Latin crucifixio, perfect passive participle crucifixus, fixed to a cross, from prefix cruci-, cross, + verb ficere, fix or do, variant form of facere, do or make ) is an ancient method of execution, whereby the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross (of various shapes) and left to hang until dead.

German scholar of religion Martin Hengel, the author of the work entitled Crucifixion (full title Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross), originally published in 1977, writes that while authors commonly regard the origins of crucifixion as coming from Persia due to the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus, the practice of impaling or nailing someone to a post or something similar to it, was also found among the Indians, Assyrians, Scythians, Taurians, Celts, Greeks, Seleucids, Romans, Britanni, Numidians and Carthaginians. The Carthaginians is commonly thought to have passed the knowledge to Romans, who then perfected the method.

II. HISTORY

While the origins of this method of execution are quite obscure, it is clear that the form of capital punishment lasted for over nearly 900 years, starting with the Persian king Darius’ (reigned 550-485 BC) crucifixion of 3000 Babylonian slaves in 519 BC and ending with Constantine in 337 AD; thus tens if not hundreds of thousands of individuals have been subjected to this cruel and humiliating form of punishment. There are records of mass executions in which hundreds of thousands of persons have died due to this practice.

It is common belief that crucifixion was only reserved for criminals, as a result of Plutarch’s passage that “each criminal condemned to death bears his cross on his back”, however literature clearly shows that this class were not the only individuals who were subjected to crucifixion. For example, Alexander the Great crucified 2000 survivors from the siege of Tyre on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Condemned Roman citizens were usually exempt from crucifixion (like feudal nobles from hanging, dying more honorably by decapitation) except for major crimes against the state, such as high treason.

The goal of Roman crucifixion was not just to kill the criminal, but also to mutilate and dishonour the body of the condemned. In ancient tradition, an honourable death required burial; leaving a body on the cross, so as to mutilate it and prevent its burial, was a grave dishonour.

Under ancient Roman penal practice, crucifixion was also a means of exhibiting the criminal’s low social status. It was the most dishonourable death imaginable, originally reserved for slaves, hence still called "supplicium servile" by Seneca, later extended to provincial freedmen of obscure station ('humiles'). The citizen class of Roman society were almost never subject to capital punishments; instead, they were fined or exiled. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus mentions Jews of high rank who were crucified, but this was to point out that their status had been taken away from them.

criminal’s low social status. It was the most dishonourable death imaginable, originally reserved for slaves, hence still called "supplicium servile" by Seneca, later extended to provincial freedmen of obscure station ('humiles'). The citizen class of Roman society were almost never subject to capital punishments; instead, they were fined or exiled. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus mentions Jews of high rank who were crucified, but this was to point out that their status had been taken away from them.

Control of one’s own body was vital in the ancient world. Capital punishment took away control over one’s own body, thereby implying a loss of status and honor. The Romans often broke the prisoner's legs to hasten death and usually (with a few known exceptions) forbade burial.

III. METHODS OF CRUCIFIXION

Crucifixion was literally a death that was ‘excruciating’ (from the Latin word ‘ex cruces’, “out of crucifying”), gruesome (hence dissuading against the crimes punishable by it), and public (hence the expression “to nail to the cross”), using whatever means expedient for that goal. The methods varied considerably with location and with time period.

The Greek and Latin words corresponding to “crucifixion” covered a wide range of meaning, from impaling on a stake to affixing on a tree, to a mere upright pole (a ‘crux simplex’) or to a combination of an upright stake (‘stipes’ in Latin) and a crossbeam (‘patibulum’).

If a crossbeam is used, the victim was forced to carry it on his shoulders, which would have been torn open by a brutal scourging, to the place of execution. The Roman historian Tacitus records that the city of Rome had a specific place for carrying out executions, situated outside the Esquiline Gate, and a specific area reserved for the execution of slaves by crucifixion.

A. SCOURGING Scourging the victim was a legal preliminary to every Roman execution, and only women and Roman senators or soldiers (except in eases of desertion) were exempt. The usual instrument was a short whip (known as a flagellum or flagrum, seen at right) with several single or braided leather thongs of variable lengths, in which small iron or lead balls or sharp pieces of sheep bones were tied at intervals.

Scourging the victim was a legal preliminary to every Roman execution, and only women and Roman senators or soldiers (except in eases of desertion) were exempt. The usual instrument was a short whip (known as a flagellum or flagrum, seen at right) with several single or braided leather thongs of variable lengths, in which small iron or lead balls or sharp pieces of sheep bones were tied at intervals.

For scourging, the man was first stripped of his clothing, and his hands were tied to an upright post.

The poet Horace refers to the horribile flagellum (horrible whip) in his Satires, calling for the end of its use. Typically, the one to be punished was stripped naked and bound to a low pillar so that he could bend over it, or chained to an upright pillar as to be stretched out.

The back, buttocks, and legs were flogged either by two Roman officials known as lictors (from the Latin verb ligare, which means "to bind", said to refer to the fasces that they carried) or by one who alternated positions (some reports even indicate scourgings with four or six lictores). The severity of the scourging depended on the disposition of the lictores and was intended to weaken the victim to a state just short of collapse or death.

There was no limit to the number of blows inflicted — this was left to the lictores to decide, though they were normally not supposed to kill the victim. Nonetheless, Livy, Suetonius and Josephus report cases of flagellation where victims died while still bound to the post. Josephus also states that, at the Siege of Jerusalem at 70 AD (Jewish War 5.11), Jews who were captured by Titus' forces "were first whipped, and then tormented with all sorts of tortures, before they died, and were then crucified before the wall of the city. This miserable procedure made Titus greatly to pity them, while they caught every day five hundred Jews; nay, some days they caught more; yet it did not appear to be safe for him to let those that were taken by force go their way, and to set a guard over so many he saw would be to make such as great deal them useless to him. "

and Josephus report cases of flagellation where victims died while still bound to the post. Josephus also states that, at the Siege of Jerusalem at 70 AD (Jewish War 5.11), Jews who were captured by Titus' forces "were first whipped, and then tormented with all sorts of tortures, before they died, and were then crucified before the wall of the city. This miserable procedure made Titus greatly to pity them, while they caught every day five hundred Jews; nay, some days they caught more; yet it did not appear to be safe for him to let those that were taken by force go their way, and to set a guard over so many he saw would be to make such as great deal them useless to him. "

Flagellation was so severe that it was referred to as "half death" by some authors and apparently, many died shortly thereafter (some survivors were even reported to have gone mad due to the intensity of the scourging). Cicero reports in In Verrem (II.5), "pro mortuo sublatus, perbrevi postea est mortuus" ("taken away for a dead man, shortly thereafter he was dead"). Often the victim was turned over to allow flagellation on the chest, though this proceeded with more caution, as the possibility of inflicting a fatal blow was much greater.

As Pontius Pilate was only the Prefect/Equestrian Procurator of Iudeaea Region (from 26-36 A.D.), he might have had no true lictor of his own, hence regular soldiers might have administered the scourging in place of lictores.

After the scourging, the soldiers often taunted their victim. In Jesus' situation, this took the form of plaiting thorns (several prickly or thorny shrubs found in Palestine, especially the Paliurus aculeatus, Zizyphus Spina-Christi, and Zizyphus vulgaris may have served for the purpose) into a sort of 'crown' (the Gospels use the Greek word stephanon, which usually implies a wreath or garland of some sort; however some think that it is likely that the crown was a sort of 'cap' that covered the whole head, as in the illustration at right), dressing him in a purple (so say Mark and John) or scarlet (Matthew) cloak (Matthew and Mark used the Greek word chlamys, which was originally a sort of cloak worn by Greek soldiers made from a rectangle of woollen material about the size of a blanket, typically bordered, and was usually pinned at the right shoulder while John used the word himation, which was a type of cloak worn over the tunic or chiton), in order to mock him as King of the Jews. In addition, he was also provided a reed (kalamos) for a sceptre, which was later used to beat him (Matt. 27:30). However, once the soldiers got tired of this sport, they took off the robe, "dressed him in his own clothes, and led him off to crucify him."

B. TO THE PLACE OF EXECUTION It was customary for the condemned man to carry his own cross from the flogging post to the site of crucifixion outside the city walls. He was usually naked, unless this was prohibited by local customs. Since the weight of the entire cross was probably well over 300 pounds (136 kilograms), only the crossbar was carried. The patibulum, weighing 75-125 pounds (35-60 kg). was placed across the nape of the victim’s neck and balanced along both shoulders. Usually, the outstretched arms then were tied to the crossbar.

It was customary for the condemned man to carry his own cross from the flogging post to the site of crucifixion outside the city walls. He was usually naked, unless this was prohibited by local customs. Since the weight of the entire cross was probably well over 300 pounds (136 kilograms), only the crossbar was carried. The patibulum, weighing 75-125 pounds (35-60 kg). was placed across the nape of the victim’s neck and balanced along both shoulders. Usually, the outstretched arms then were tied to the crossbar.

The processional to the site of crucifixion was led by execution teams composed of four soldiers, headed by a centurion, with the condemned man placed in the middle of the hollow square of the four soldiers.

A herald carried a sign (titulus, epigraphe) on which the condemned man’s name and crime were displayed; alternatively, it would have been hung around the victim's neck. The board was said to be whitened with gypsum while the lettering was in black; alternatively, the lettering was done with gypsum. The description of guilt written thereon was usually made to be as brief and as concise as possible; the Gospel's record that Jesus' titulus merely contained his name and his crime ("the King of the Jews"). Eusebius (Ecclesiastical History 5.1) recorded a Christian martyr named Attalus who was led to the ampitheatre to be killed, with a placard being carried before him which said simply: "This is Attalus the Christian."

At the site of execution, the victim stripped of his clothing (if any) and, at least in Palestine, was given a bitter drink of wine mixed with myrrh (gall) as a mild analgesic to help deaden the pain. The criminal was then thrown to the ground on his back, with his arms outstretched along the patibulum. Any article of clothing belonging to the victim became the property of the party of soldiers in charge of the execution, as per the law; thus, the soldiers drew lots for Jesus' clothes.

There was no 'set' posture for someone being crucified; soldiers usually crucified victims in various postures and positions (Josephus mentions that during the Siege of Jerusalem, soldiers crucified those they caught "one after one way, and another after another" to amuse themselves).

Upright posts would have presumably been erected and fixed permanently in such places, and the crossbeam, with the condemned man perhaps already nailed to it, would then be attached to the post. To prolong the crucifixion process, a horizontal wooden block or plank serving as a crude seat (known as a sedile or sedulum), was often attached midway down the stipes.

C. TYING OR NAILING TO THE CROSS?

The condemned man may sometimes have been attached to the cross by tying him  securely there (some scholars have, in fact, argued that crucifixion was actually a bloodless form of death and that tying the victim was the rule), but nails are mentioned by Josephus, who states that, again during the Siege of Jerusalem, “the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.”

securely there (some scholars have, in fact, argued that crucifixion was actually a bloodless form of death and that tying the victim was the rule), but nails are mentioned by Josephus, who states that, again during the Siege of Jerusalem, “the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.”

Therefore, other scholars such as Hengel, who here takes along with Hewitt (1932) have argued that nailing the victim by his hands and feet was the rule and tying him to the cross was the exception.

In Roman times iron was expensive; thus, nails from a crucifixion were usually removed from the dead body and reused over and over to cut the costs. Also, objects used in the execution of criminals, such as nails or ropes from a crucifixion were frequently sought as amulets by many people, and was thus removed from the victim following their death.

This is attested to by a passage in the Mishna (Tractate Sabbath 6.10) which states that both Jews and Amorites (a sort of 'codeword' for non-Jews) may carry a nail from a crucifixion, a tooth from a jackal and an egg from a locust as a means of healing:

MISHNA IX: It is permitted to go out with eggs of grasshoppers or with the tooth of a fox or a nail from the gallows where a man was hanged, as medical remedies. Such is the decision of R. Meir, but the sages prohibit the using of these things even on week days, for fear of imitating the Amorites.

GEMARA: The eggs of grasshoppers as a remedy for toothache; the tooth of a fox as a remedy for sleep, viz., the tooth of a live fox to prevent sleep and of a dead one to cause sleep; the nail from the gallows where a man was hanged as a remedy for swelling.

"As medical remedies," such is the decision of R. Meir. Abayi and Rabha both said: "Anything (intended) for a medical remedy, there is no apprehension of imitating the Amorites; hence, if not intended as a remedy there is apprehension of imitating the Amorites? But were we not taught that a tree which throws off its fruit, it is permitted to paint it and lay stones around it? It is right only to lay stones around it in order to weaken its strength, but what remedy is painting it? Is it not imitating the Amorites? (Nay) it is only that people may see it and pray for mercy. We have learned in a Boraitha: It is written: "Unclean, unclean, shall he call out [Leviticus, 13:45]." (To what purpose?) That one must make his troubles known to his fellow-men, that they may pray for his relief."

As this Mishnaic passage mentions both Jews and non-Jews carrying these objects one can infer the power of these amulets and their scarcity in the archaeological record. Not only Jewish sources attest to the power of these objects; Pliny in Naturalis Historia (28.11) wrote that:

...So, too, in cases of quartan fever, they take a fragment of a nail from a cross, or else a piece of a halter that has been used for crucifixion, and, after wrapping it in wool, attach it to the patient's neck; taking care, the moment he has recovered, to conceal it in some hole to which the light of the sun cannot penetrate...

Perhaps, however, the number of the individuals crucified may determine the manner in which the execution took form. For example, during the Third Servile War (led by the slave Spartacus), which happened in 73-71 BC, 6600 prisoners of war were crucified along the Via Appia between the cities of Rome and Capua, it would seem plausible that the most quick and efficient manner of death was employed; namely, to simply tie the victim to the tree or cross with his hands suspended directly over his head, causing death within a few minutes, or perhaps an hour if the victims’ feet were not nailed or tied down.