I. INTRODUCTION

I. INTRODUCTIONCrucifixion (from Latin

crucifixio, perfect passive participle crucifixus, fixed to a cross, from prefix

cruci-, cross, + verb

ficere, fix or do, variant form of

facere, do or make ) is an ancient method of execution, whereby the condemned person is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross (of various shapes) and left to hang until dead.

German scholar of religion Martin Hengel, the author of the work entitled Crucifixion (full title Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross), originally published in 1977, writes that while authors commonly regard the origins of crucifixion as coming from Persia due to the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus, the practice of impaling or nailing someone to a post or something similar to it, was also found among the Indians, Assyrians, Scythians, Taurians, Celts, Greeks, Seleucids, Romans, Britanni, Numidians and Carthaginians. The Carthaginians is commonly thought to have passed the knowledge to Romans, who then perfected the method.

II. HISTORY

While the origins of this method of execution are quite obscure, it is clear that the form of capital punishment lasted for over nearly 900 years, starting with the Persian king Darius’ (reigned 550-485 BC) crucifixion of 3000 Babylonian slaves in 519 BC and ending with Constantine in 337 AD; thus tens if not hundreds of thousands of individuals have been subjected to this cruel and humiliating form of punishment. There are records of mass executions in which hundreds of thousands of persons have died due to this practice.

It is common belief that crucifixion was only reserved for criminals, as a result of Plutarch’s passage that “each criminal condemned to death bears his cross on his back”, however literature clearly shows that this class were not the only individuals who were subjected to crucifixion. For example, Alexander the Great crucified 2000 survivors from the siege of Tyre on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Condemned Roman citizens were usually exempt from crucifixion (like feudal nobles from hanging, dying more honorably by decapitation) except for major crimes against the state, such as high treason.

The goal of Roman crucifixion was not just to kill the criminal, but also to mutilate and dishonour the body of the condemned. In ancient tradition, an honourable death required burial; leaving a body on the cross, so as to mutilate it and prevent its burial, was a grave dishonour.

Under ancient Roman penal practice, crucifixion was also a means of exhibiting the criminal’s low social status. It was the most dishonourable death imaginable, originally reserved for slaves, hence still called "supplicium servile" by Seneca, later extended to provincial freedmen of obscure station ('humiles'). The citizen class of Roman society were almost never subject to capital punishments; instead, they were fined or exiled. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus mentions Jews of high rank who were crucified, but this was to point out that their status had been taken away from them.

criminal’s low social status. It was the most dishonourable death imaginable, originally reserved for slaves, hence still called "supplicium servile" by Seneca, later extended to provincial freedmen of obscure station ('humiles'). The citizen class of Roman society were almost never subject to capital punishments; instead, they were fined or exiled. The Jewish-Roman historian Josephus mentions Jews of high rank who were crucified, but this was to point out that their status had been taken away from them.

Control of one’s own body was vital in the ancient world. Capital punishment took away control over one’s own body, thereby implying a loss of status and honor. The Romans often broke the prisoner's legs to hasten death and usually (with a few known exceptions) forbade burial.

III. METHODS OF CRUCIFIXION

Crucifixion was literally a death that was ‘excruciating’ (from the Latin word ‘ex cruces’, “out of crucifying”), gruesome (hence dissuading against the crimes punishable by it), and public (hence the expression “to nail to the cross”), using whatever means expedient for that goal. The methods varied considerably with location and with time period.

The Greek and Latin words corresponding to “crucifixion” covered a wide range of meaning, from impaling on a stake to affixing on a tree, to a mere upright pole (a ‘crux simplex’) or to a combination of an upright stake (‘stipes’ in Latin) and a crossbeam (‘patibulum’).

If a crossbeam is used, the victim was forced to carry it on his shoulders, which would have been torn open by a brutal scourging, to the place of execution. The Roman historian Tacitus records that the city of Rome had a specific place for carrying out executions, situated outside the Esquiline Gate, and a specific area reserved for the execution of slaves by crucifixion.

A. SCOURGING

Scourging the victim was a legal preliminary to every Roman execution, and only women and Roman senators or soldiers (except in eases of desertion) were exempt. The usual instrument was a short whip (known as a flagellum or flagrum, seen at right) with several single or braided leather thongs of variable lengths, in which small iron or lead balls or sharp pieces of sheep bones were tied at intervals.

Scourging the victim was a legal preliminary to every Roman execution, and only women and Roman senators or soldiers (except in eases of desertion) were exempt. The usual instrument was a short whip (known as a flagellum or flagrum, seen at right) with several single or braided leather thongs of variable lengths, in which small iron or lead balls or sharp pieces of sheep bones were tied at intervals.

For scourging, the man was first stripped of his clothing, and his hands were tied to an upright post.

The poet Horace refers to the horribile flagellum (horrible whip) in his Satires, calling for the end of its use. Typically, the one to be punished was stripped naked and bound to a low pillar so that he could bend over it, or chained to an upright pillar as to be stretched out.

The back, buttocks, and legs were flogged either by two Roman officials known as lictors (from the Latin verb ligare, which means "to bind", said to refer to the fasces that they carried) or by one who alternated positions (some reports even indicate scourgings with four or six lictores). The severity of the scourging depended on the disposition of the lictores and was intended to weaken the victim to a state just short of collapse or death.

There was no limit to the number of blows inflicted — this was left to the lictores to decide, though they were normally not supposed to kill the victim. Nonetheless, Livy, Suetonius and Josephus report cases of flagellation where victims died while still bound to the post. Josephus also states that, at the Siege of Jerusalem at 70 AD (Jewish War 5.11), Jews who were captured by Titus' forces "were first whipped, and then tormented with all sorts of tortures, before they died, and were then crucified before the wall of the city. This miserable procedure made Titus greatly to pity them, while they caught every day five hundred Jews; nay, some days they caught more; yet it did not appear to be safe for him to let those that were taken by force go their way, and to set a guard over so many he saw would be to make such as great deal them useless to him. "

and Josephus report cases of flagellation where victims died while still bound to the post. Josephus also states that, at the Siege of Jerusalem at 70 AD (Jewish War 5.11), Jews who were captured by Titus' forces "were first whipped, and then tormented with all sorts of tortures, before they died, and were then crucified before the wall of the city. This miserable procedure made Titus greatly to pity them, while they caught every day five hundred Jews; nay, some days they caught more; yet it did not appear to be safe for him to let those that were taken by force go their way, and to set a guard over so many he saw would be to make such as great deal them useless to him. "

Flagellation was so severe that it was referred to as "half death" by some authors and apparently, many died shortly thereafter (some survivors were even reported to have gone mad due to the intensity of the scourging). Cicero reports in In Verrem (II.5), "pro mortuo sublatus, perbrevi postea est mortuus" ("taken away for a dead man, shortly thereafter he was dead"). Often the victim was turned over to allow flagellation on the chest, though this proceeded with more caution, as the possibility of inflicting a fatal blow was much greater.

As Pontius Pilate was only the Prefect/Equestrian Procurator of Iudeaea Region (from 26-36 A.D.), he might have had no true lictor of his own, hence regular soldiers might have administered the scourging in place of lictores.

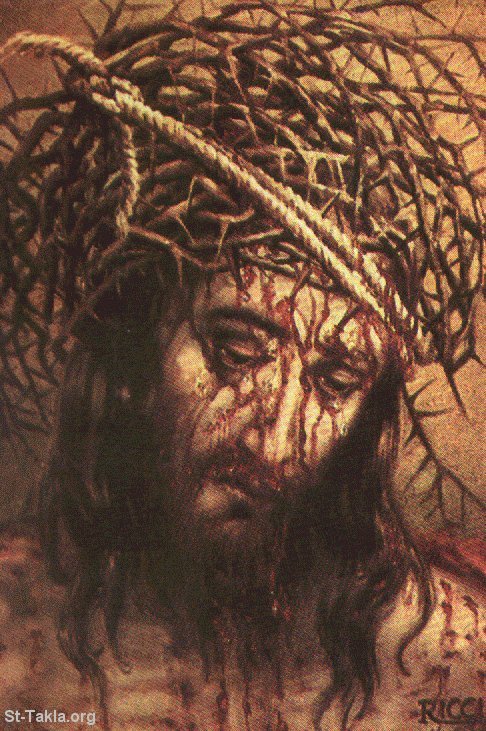

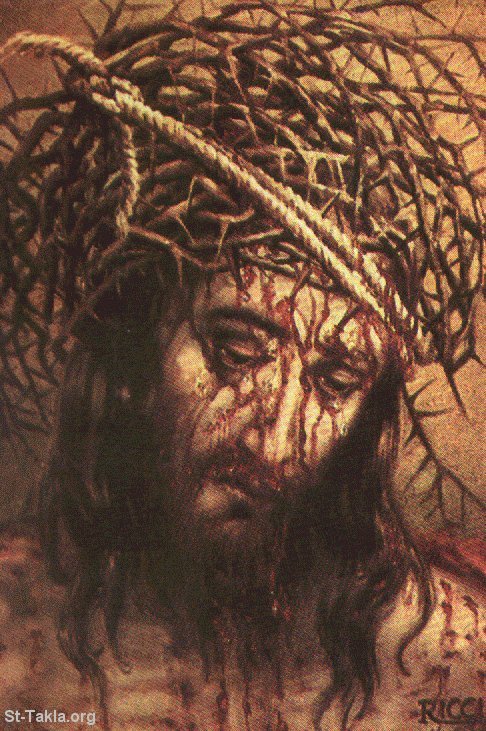

After the scourging, the soldiers often taunted their victim. In Jesus' situation, this took the form of plaiting thorns (several prickly or thorny shrubs found in Palestine, especially the Paliurus aculeatus, Zizyphus Spina-Christi, and Zizyphus vulgaris may have served for the purpose) into a sort of 'crown' (the Gospels use the Greek word stephanon, which usually implies a wreath or garland of some sort; however some think that it is likely that the crown was a sort of 'cap' that covered the whole head, as in the illustration at right), dressing him in a purple (so say Mark and John) or scarlet (Matthew) cloak (Matthew and Mark used the Greek word chlamys, which was originally a sort of cloak worn by Greek soldiers made from a rectangle of woollen material about the size of a blanket, typically bordered, and was usually pinned at the right shoulder while John used the word himation, which was a type of cloak worn over the tunic or chiton), in order to mock him as King of the Jews. In addition, he was also provided a reed (kalamos) for a sceptre, which was later used to beat him (Matt. 27:30). However, once the soldiers got tired of this sport, they took off the robe, "dressed him in his own clothes, and led him off to crucify him."

B. TO THE PLACE OF EXECUTION

It was customary for the condemned man to carry his own cross from the flogging post to the site of crucifixion outside the city walls. He was usually naked, unless this was prohibited by local customs. Since the weight of the entire cross was probably well over 300 pounds (136 kilograms), only the crossbar was carried. The patibulum, weighing 75-125 pounds (35-60 kg). was placed across the nape of the victim’s neck and balanced along both shoulders. Usually, the outstretched arms then were tied to the crossbar.

It was customary for the condemned man to carry his own cross from the flogging post to the site of crucifixion outside the city walls. He was usually naked, unless this was prohibited by local customs. Since the weight of the entire cross was probably well over 300 pounds (136 kilograms), only the crossbar was carried. The patibulum, weighing 75-125 pounds (35-60 kg). was placed across the nape of the victim’s neck and balanced along both shoulders. Usually, the outstretched arms then were tied to the crossbar.

The processional to the site of crucifixion was led by execution teams composed of four soldiers, headed by a centurion, with the condemned man placed in the middle of the hollow square of the four soldiers.

A herald carried a sign (titulus, epigraphe) on which the condemned man’s name and crime were displayed; alternatively, it would have been hung around the victim's neck. The board was said to be whitened with gypsum while the lettering was in black; alternatively, the lettering was done with gypsum. The description of guilt written thereon was usually made to be as brief and as concise as possible; the Gospel's record that Jesus' titulus merely contained his name and his crime ("the King of the Jews"). Eusebius (Ecclesiastical History 5.1) recorded a Christian martyr named Attalus who was led to the ampitheatre to be killed, with a placard being carried before him which said simply: "This is Attalus the Christian."

At the site of execution, the victim stripped of his clothing (if any) and, at least in Palestine, was given a bitter drink of wine mixed with myrrh (gall) as a mild analgesic to help deaden the pain. The criminal was then thrown to the ground on his back, with his arms outstretched along the patibulum. Any article of clothing belonging to the victim became the property of the party of soldiers in charge of the execution, as per the law; thus, the soldiers drew lots for Jesus' clothes.

There was no 'set' posture for someone being crucified; soldiers usually crucified victims in various postures and positions (Josephus mentions that during the Siege of Jerusalem, soldiers crucified those they caught "one after one way, and another after another" to amuse themselves).

Upright posts would have presumably been erected and fixed permanently in such places, and the crossbeam, with the condemned man perhaps already nailed to it, would then be attached to the post. To prolong the crucifixion process, a horizontal wooden block or plank serving as a crude seat (known as a sedile or sedulum), was often attached midway down the stipes.

C. TYING OR NAILING TO THE CROSS?

The condemned man may sometimes have been attached to the cross by tying him  securely there (some scholars have, in fact, argued that crucifixion was actually a bloodless form of death and that tying the victim was the rule), but nails are mentioned by Josephus, who states that, again during the Siege of Jerusalem, “the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.”

securely there (some scholars have, in fact, argued that crucifixion was actually a bloodless form of death and that tying the victim was the rule), but nails are mentioned by Josephus, who states that, again during the Siege of Jerusalem, “the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.”

Therefore, other scholars such as Hengel, who here takes along with Hewitt (1932) have argued that nailing the victim by his hands and feet was the rule and tying him to the cross was the exception.

In Roman times iron was expensive; thus, nails from a crucifixion were usually removed from the dead body and reused over and over to cut the costs. Also, objects used in the execution of criminals, such as nails or ropes from a crucifixion were frequently sought as amulets by many people, and was thus removed from the victim following their death.

This is attested to by a passage in the Mishna (Tractate Sabbath 6.10) which states that both Jews and Amorites (a sort of 'codeword' for non-Jews) may carry a nail from a crucifixion, a tooth from a jackal and an egg from a locust as a means of healing:

MISHNA IX: It is permitted to go out with eggs of grasshoppers or with the tooth of a fox or a nail from the gallows where a man was hanged, as medical remedies. Such is the decision of R. Meir, but the sages prohibit the using of these things even on week days, for fear of imitating the Amorites.

GEMARA: The eggs of grasshoppers as a remedy for toothache; the tooth of a fox as a remedy for sleep, viz., the tooth of a live fox to prevent sleep and of a dead one to cause sleep; the nail from the gallows where a man was hanged as a remedy for swelling.

"As medical remedies," such is the decision of R. Meir. Abayi and Rabha both said: "Anything (intended) for a medical remedy, there is no apprehension of imitating the Amorites; hence, if not intended as a remedy there is apprehension of imitating the Amorites? But were we not taught that a tree which throws off its fruit, it is permitted to paint it and lay stones around it? It is right only to lay stones around it in order to weaken its strength, but what remedy is painting it? Is it not imitating the Amorites? (Nay) it is only that people may see it and pray for mercy. We have learned in a Boraitha: It is written: "Unclean, unclean, shall he call out [Leviticus, 13:45]." (To what purpose?) That one must make his troubles known to his fellow-men, that they may pray for his relief."

As this Mishnaic passage mentions both Jews and non-Jews carrying these objects one can infer the power of these amulets and their scarcity in the archaeological record. Not only Jewish sources attest to the power of these objects; Pliny in Naturalis Historia (28.11) wrote that:

...So, too, in cases of quartan fever, they take a fragment of a nail from a cross, or else a piece of a halter that has been used for crucifixion, and, after wrapping it in wool, attach it to the patient's neck; taking care, the moment he has recovered, to conceal it in some hole to which the light of the sun cannot penetrate...

Perhaps, however, the number of the individuals crucified may determine the manner in which the execution took form. For example, during the Third Servile War (led by the slave Spartacus), which happened in 73-71 BC, 6600 prisoners of war were crucified along the Via Appia between the cities of Rome and Capua, it would seem plausible that the most quick and efficient manner of death was employed; namely, to simply tie the victim to the tree or cross with his hands suspended directly over his head, causing death within a few minutes, or perhaps an hour if the victims’ feet were not nailed or tied down.

REVELATION 12:7-12a

REVELATION 12:7-12a You should be aware that the word “angel” denotes a function rather than a nature. Those holy spirits of heaven have indeed always been spirits. They can only be called angels when they deliver some message. Moreover, those who deliver messages of lesser importance are called angels; and those who proclaim messages of supreme importance are called archangels. And so it was that not merely an angel but the archangel Gabriel was sent to the Virgin Mary. It was only fitting that the highest angel should come to announce the greatest of all messages.

You should be aware that the word “angel” denotes a function rather than a nature. Those holy spirits of heaven have indeed always been spirits. They can only be called angels when they deliver some message. Moreover, those who deliver messages of lesser importance are called angels; and those who proclaim messages of supreme importance are called archangels. And so it was that not merely an angel but the archangel Gabriel was sent to the Virgin Mary. It was only fitting that the highest angel should come to announce the greatest of all messages.

As a general rule of thumb, most of these early representations are not depictions made by Christians, who still didn't depict the Crucifixion overtly during this time period, but were usually created by non-Christians and/or Gnostics.

As a general rule of thumb, most of these early representations are not depictions made by Christians, who still didn't depict the Crucifixion overtly during this time period, but were usually created by non-Christians and/or Gnostics.